Tumor Heterogeneity

Lecture, Medizinische Fakultät, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, 2024

This lecture provides a brief introduction to the topic of tumor heterogeneity from the perspective of a mathematical oncologist.

Learing goals: to be able to distinguish forms of tumor heterogeneity, understand that they are a direct result of the complex process of cancer evolution, and to quantify heterogeneity from sequencing or cell classification (labeling) data using at least two different approaches.

You can find the slides (in German) here.

What are the origins and importance of tumor heterogeneity?

Tumor heterogeneity can result from diversification during the complex process of cancer evolution

Diversification can result from genetic and epigenetic mutations and genetic instability

Tumor heterogeneity is believed to be responsible for the evolution of both de novo and preexisting resistance to treatment

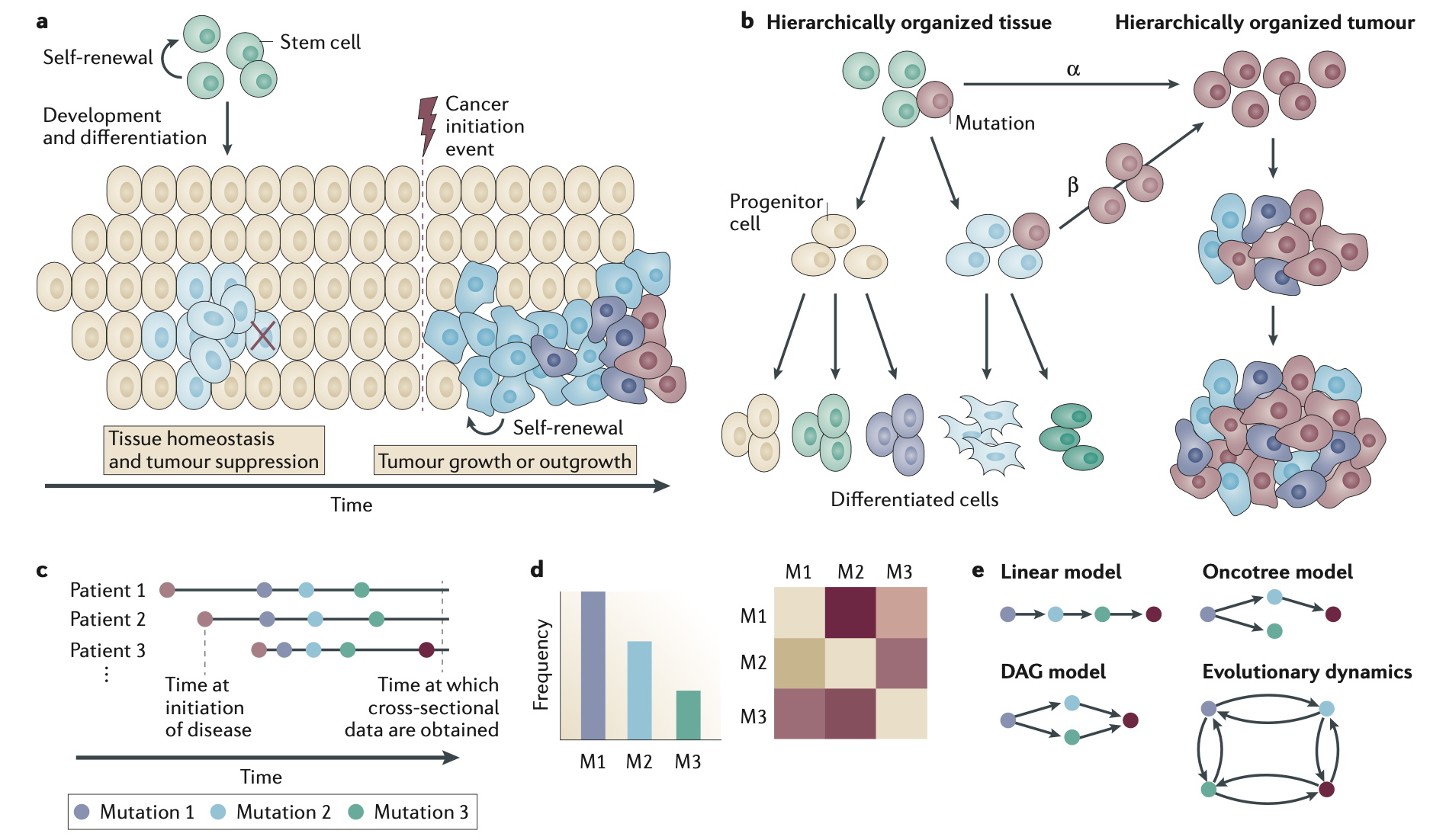

Tumor initiation and progression, from PMID: 26597528

Levels of tumor heterogeneity

Interpatient heterogeneity: Cancer cells of different patients can vary dramatically

Intratumor heterogeneity: Cancer cells of the same patient’s tumor can also vary dramatically

Intertumor heterogeneity: Cancer cells of different sites within one patient, e.g., from primary tumor and metastasis, can be different, but some metastases can be much more homogeneous again, see PMID: 32451459

To understand tumor heterogeneity, we need to understand cancer evolution

Cancer arises in the process of somatic evolution, that is, through spontaneous diversification and selection in cell populations of the human body.

A reiteraive process of expansion, diversificaiton, selection can take place.

By the process of clonal evolution, tumors harvest heterogeneity, depending on the mode of selection (e.g., neutral evolution, clonal interference, punctuated equilibrium, spatially isolated selection events). See this review

The role of plasticity

There is also evidence of diversification of cellular behavior, called plasticity

The increasing complexity of a tumor, e.g., driven by disorganized vasculature and conflicting signals to the immune system, opens the door for cellular plasticity programs to persist and for the coexistence of cell phenotypes

Phenotypic plasticity can result in niches within which cancer cells may better survive therapy and evolve long-term resistance

Plasticity does not only affect cancer cells, but also the cancer infiltrating stroma and immmune cells, e.g., fibroblasts and T lymphocytes.

Cancer also may inherit some of the tissue’s levels of differentiation, e.g., in the form of cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are uniquely capable of recapitulating a tumor and give rise to multiple lineages that can contribute in phenotypic tumor heterogeneity.

Tumor heterogeneity contributes to resistance to therapy

Radiotherapy: non-dividing persister (cancer stem) cells may not be affected as much

Chemotherapy: Genetic mutations and phenotypic plasticity can lead to low responses in cancer subpopulations

Targeted therapy: Persister cells can lead to de novo resistance; low-frequency pre-existing resistance is eventually selected (and may become more aggressive on the way)

Immune therapy: Immune-evading pathways are enriched during treatment; spatial constraints may hinder immune cell killing

Measuring tumor heterogeneity

Diversity index measures, such as Shannon index or related quantities, see generalized diversity

For example, using the Shannon index, Almendro et al. found that intratumor genetic diversity was tumor-subtype specific in breast cancers (comparing Luminal A/B, Triple negative, and Her2+ cancers). Yet, diversity did not change during treatment in tumors with partial or no response.

Diversity can also be assessed using median differences of allele frequencies, e.g., using “Mutant Allele Tumor Heterogeneity” (MATH), see PMID: 26840267

Literature

Marusyk A, Polyak K. Tumor heterogeneity: causes and consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010. PMID: 19931353

Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature. 2013. PMID: 24048065

Tabassum DP, Polyak K. Tumorigenesis: it takes a village. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015. PMID: 26156638

Morris LG et al. Pan-cancer analysis of intratumor heterogeneity as a prognostic determinant of survival. 2016. PMID: 26840267

Grzywa TM, Paskal W, Włodarski PK. Intratumor and Intertumor Heterogeneity in Melanoma. Transl Oncol. 2017. PMID: 29078205

Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018. PMID: 29115304